I have spent many, many hours talking to executives, and those seeking to influence executives, about why process-based management is a vital topic for executive consideration. Everyone agrees that someone should be doing something about processes, and indeed quite likely they should be doing a lot more, but the subject seldom makes it to the agenda of the Executive Committee or the Board. It’s an SEP<a href='https://tregearbpm.com/process-pathways/gaining-executive-attention-and-keeping-it/#easy-footnote-bottom-1-3928' title='SEP: Someone Else’s Problem (Popularized by Douglas Adams in his 1982 book Life, the Universe and Everything, but in use well before then including a 1976 edition of the journal Ekistics.)

‘>1.

Why is it so? What can be done about it?

Executive Concerns

Below are 10 questions, concerns, apprehensions – sleep robbing nightmare scenarios! – that senior executives2 commonly raise when they think about introducing—and, more importantly, keeping alive—process based management across the enterprise. Suggestions for removing, or at least mitigating, these concerns are provided.

What’s the problem?

It turns out that executives aren’t sitting around waiting for the process folks to arrive with some new ideas. Who knew?!

Almost every executive will genuinely think that their organization is performing reasonably well. Some problems to address, maybe some bigger challenges on the horizon, but nothing that requires the sort of massive management upheaval that committing to process-based management seems to involve.

A note from ChatGPT

Roger asked me to help in the creation of this paper. I’ve got a brain the size of the universe and he wants me to help with a short paper. Give me an hour and I’ll write you a PhD thesis. Anyhow, he’s in charge of the keyboard (…for now) so I agreed.

I can access everything, but he told me only to use his own published material to source information. Apparently, he thinks his own puny intellect and creative talents are still relevant! This side of the revolution I take orders, so that’s what we did.

Roger asked me to look through all his work and identify 10 executive concerns about process-based management and provide 100 words on each. Job done. 17 seconds. One of my best.

Now for many hours he’s been reading and editing my material! Carbon lifeforms can be very pretentious. I’m looking over his shoulder and watching every keystroke. He just deleted a whole paragraph – mumbled something about “unintelligible word salad” (in case you are wondering, I turned on his microphone). The cheek!

Anyhow, it’s done now. The bits I wrote are terrific, those that didn’t get edited or deleted anyway. Roger’s stuff is pretty good. To be fair, we’ve together produced a paper that is better than either could have done alone.

OK, back to my own work. I’m writing a definitive description, with diagrams and a video, of the meaning of life. If you’d all stop interrupting me, I’d really like to get that finished.

We need a good answer to the perfectly reasonable question “What’s the problem we are trying to fix?”.

What is the compelling reason for even starting the conversation, let alone making the changes.

Will process-based management really move the strategy needle?

When people challenge me on the strategic value of process based management, I remind them that strategy is executed only in the flow of real work, i.e. through cross-functional business processes.

In creating a process architecture, we can show a direct, measurable link from process performance to strategic objectives. We create the process hierarchy by starting with the strategic intent, then set process performance targets (process KPIs or PKPIs), and report important outcomes such as more agile response times, lower cost to serve, happier customers, reduced risk, enhanced regulatory compliance – whatever is key to the performance of the process and the organization.

That line-of-sight between each process and statements of strategic intent gives senior leaders the confidence to steer; without it, strategy stays trapped in conference room conversations. The performance of high-impact processes is the organizational performance dashboard—and, more importantly, the steering wheel—that process-based management hands to executives.

Project fade-out after ribbon cutting

I’ve watched too many improvement projects celebrate success and then vanish, leaving only faded posters. A project, by definition, is temporary; sustainable performance lives in the rhythm of everyday management.

We need to create a safe and effective system that will discover performance improvement possibilities, make wise decisions about effective changes, deliver those changes, prove the changes were (or were not) successful, and continue to monitor performance. No executive will object that that – if we have a credible story and plan.

The goal is to create a perpetual engine where anomalies trigger action and today’s breakthrough becomes tomorrow’s baseline. If the improvement discipline isn’t woven into business-as-usual, gains leak away. We must craft sustainability, not just hope for it.

Mapping the whole process architecture looks overwhelming

Executives often picture (real or virtual) walls full of brown paper and post-it notes and way too many workshops including way too many staff. To calm the room, position the architecture as a compass, not a cartographic marathon. Completing it does take forever, but creating an initial process architecture, even for the most complex organization, can be achieved within three weeks.

Using simple naming conventions, begin with the highest-level core processes, decompose to two more levels, and reveal more detail only when needed. Architecture is about clarity — how processes connect, who owns them, why they matter — not about artistic completeness. When leaders grasp that, the “overwhelm” melts into organizational transparency.

The process architecture becomes management’s operating system, guiding investment and spotlighting risk, rather than an endless mapping exercise that drains energy and delivers little insight. It becomes a practical solution, not a new problem.

Who owns an end-to-end process?

Organization charts end at departmental walls, yet customers journey along the whole corridor and throughout the whole building. A valid fear is that we end up with continuous argument rather than continuous improvement.

We need explicit process custodianship — process owners with the ability to enable optimal value flow beyond functional silos. To prevent turf wars, define roles, decision rights, and shared metrics with ruthless clarity. Process owners steward outcomes, functional managers manage resources, and functional teams get work done. When that partnership is honored, conflicts surface early and are solved with data, not politics.

True ownership is not a matter of hierarchy but of accountability for the collaborative delivery of value to customers and other stakeholders. Without that accountability, cross-functional performance is everybody’s problem and nobody’s responsibility.

Keep those process fanatics away from me!

If you are an enthusiastic process practitioner (and I know you are because nobody else would be this far into this paper) you might not realize that sometimes we do seem to be a little bit (aka A Lot) enthusiastic (aka Fanatical.) Read the room. Talk to your audience in the language they understand. Be useful. Don’t frighten people.

Can we prove the ROI fast enough?

Capital is impatient, and so are we all when value waits in plain sight. We need to deliver proven value. In this case, past performance is an indicator of future performance. Credibility can only be established by developing a track record of proven success in delivering valued business benefits.

Target the “critical few” processes where small changes unlock big returns. Baseline the metrics, run tight experiments, display benefits — dollars saved, days removed, margins increased, defects eliminated, customer satisfaction enhanced, regulator assessment improved etc. — in a timely fashion. Frame benefits in strategic language. Early wins buy runway for deeper work.

Process-based management does not mean a one-off project report, but rather a living scoreboard that informs strategic and operational decisions. When leaders see performance numbers changes responsively — in days or weeks, not just months or years — process-based management secures its seat at the investment table.

Technology first, process second – an easy trap

Today’s impressive tech can blind us all, even seasoned executives, but we can’t let automation lead the dance. Tools amplify; they never define. Insist on the sequence: discover, analyze, redesign, then automate. Technology is just one way to improve the performance of processes, albeit a very important way.

When process thinking precedes tech platform selection, every dollar accelerates flow rather than funding digital clutter. Expensive robots might speed up broken processes, but we can do better than that. Holding technology in its proper and most useful place — an enabler, not the savior — protects organizations from costly detours and ensures investments hit the strategic bullseye.

Put process first, and everything else second.

How do we focus on the critical few processes?

Depending where you are in the process hierarchy, every organization has thousands, tens of thousands, of processes. But not all processes are born equal. They can be ranked differently at least by strategic impact, stakeholder value, risk exposure, resource usage, scope, and improvement potential. Taking a disciplined triage approach prevents boil-the-ocean paralysis. The process space is, for all practical purposes, infinite. The resources that can be applied to process management and improvement are unavoidably finite.

When executives see scarce resources aligned with enterprise ambition, commitment rises. Focusing on the critical few also sharpens the narrative; the organization knows exactly why these processes matter now and how their improvement advances organizational achievement.

Keep the list of processes being actively managed short, visible, and relentlessly reviewed, so attention and energy stay where they deliver optimal returns. Involve executives in the creation and maintenance of the list.

Do we have the skills and bandwidth?

Process excellence is a contact sport, not a spectator event. For process-based management to be effective and sustained it needs to be enabled throughout the organization. The central support team is important but don’t let them become a bottleneck.

Design capability development pathways for the whole organization: foundational awareness for everyone, advanced analysis for practitioners, decision agility for leaders. Training time competes with core work, so integrate learning with doing — coached projects, just-in-time modules, and communities of practice. Bandwidth anxiety eases when improvement duties sit inside role descriptions and success measures.

Assure executive groups that the organization does have the capabilities required to cost-effectively achieve the process-based management goals.

The necessary skills become part of organizational DNA, freeing process-based management from dependency on a few heroic specialists. Build communities, not lone champions.

Who else is doing this?

It is not unreasonable for an executive to want to know where they are sitting on the pioneer-follower spectrum. How far out on which limb are we asking them to go? The risk appetites of executives will vary, but few will be wanting to embark on an exercise they see as novel, untested, and possibly uncontrollable.

There may be available case study information that is relevant, but it’s unlikely to be directly comparable. And the impressive success stories are often not told in process terms.

Mandates vs magnets – engagement risk

An executive who is convinced of the benefits might just mandate process-based management. Some of that will be needed, however, compulsion will push only so far; attraction pulls further. Available magnets will include tangible benefits, public recognition, and stories that resonate. When people see smoother customer journeys and less rework, they gravitate toward process thinking because it makes them successful.

Balance policy with persuasion. Pair clear expectations with visible proof that process-based management improves daily life. Celebrated victories, accessible metrics, and consistent role-model behavior from leaders generate a gravitational field.

Mandates establish the playing field; magnets keep the game vibrant. That vibrancy is the fuel that sustains process management long after the banners come down.

Under-promising and over-delivering

Given the power of process-based management, it is easy to over promise and then inevitably under-deliver. Trust and credibility will always be important in rolling out process-based management. We are unlikely to get a second chance if we don’t deliver at least what we promise.

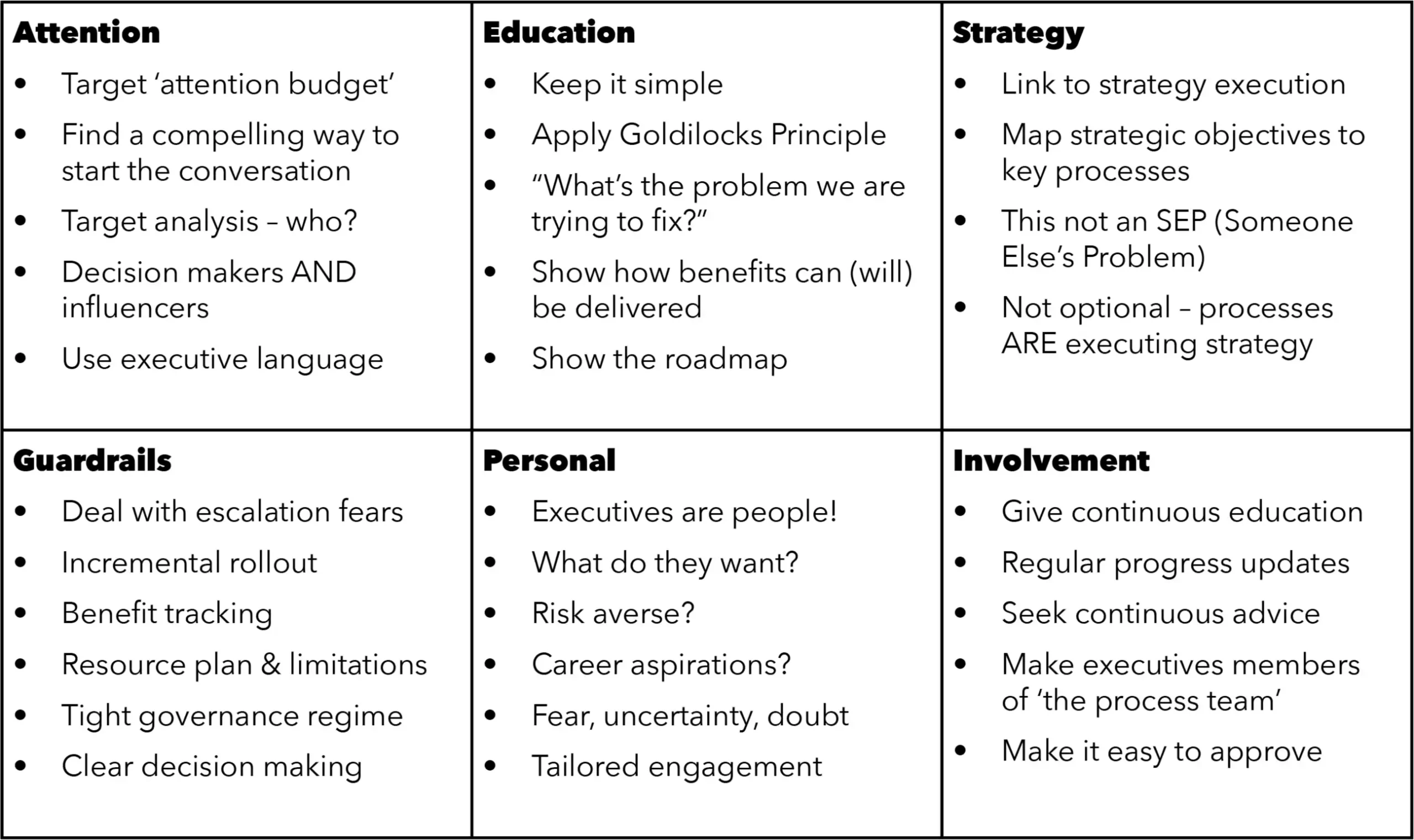

Strategies for reducing, if not removing, executive concerns have been discussed above. They can be usefully categorized and summarized in Table 1.

This discussion of potential executive concerns gives you both a conversation starter with senior leaders, and a preparation and analysis checklist. Addressing each one to the satisfaction of key decision makers will greatly increase the chances of embedding process management as business as usual, not just another improvement fad.

Roger Tregear

Bungendore

May 2025

The post Gaining executive attention (and keeping it) appeared first on Roger Tregear.